The Liberal Arts Are Dying Because Liberalism is Dying

Negative Capability Is Rarer Than We Thought

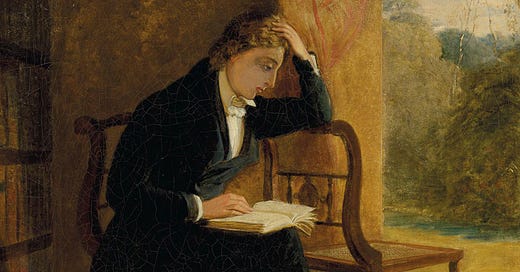

“The only means of strengthening one’s intellect is to make up one’s mind about nothing—to let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts, not a select party.”

—John Keats

Keats calls the ability to entertain doubt and uncertainty without going mad or becoming hyper-rational in reaction, “negative capability.” Discomfort is not just generative for the po…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to What Is Called Thinking? to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.