Is Precise Language (Always) Good? [Part II]

On David Foster Wallace's Radically Condensed History of Postindustrial Life

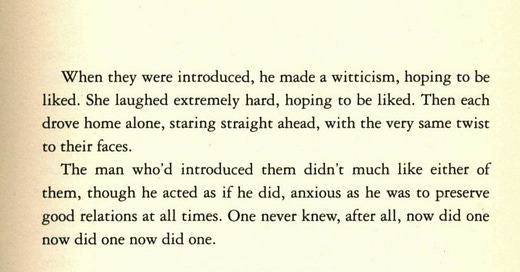

Continuing on my original reflections on the virtues of imprecise language, I’d like to examine a moment in a short short story by David Foster Wallace that strikes me as both good and precisely imprecise:

Much could be said of this “radically condensed history,” but let’s focus on the last sentence: “One never knew, after all, now did one now did one no…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to What Is Called Thinking? to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.